“Because this world is 66% Then and 33% Now,” writes poet David Berman in his poem Cassette County. The poem starts in praise of “the interval called the hangover,” and on the way there's mostly trouble. What it portrays is a complete domination of the Then over the Now, an instance when “even this glass of water seems complicated now.”

There is many a philosophy of life/religion predicated on the Power of Now (this one springs to mind), but there are likely to be more people still who shudder and shiver at this spiritual claptrap. Regardless, there is many a thing to say about this dichotomy of what is and what has passed.

The above poem is not the only example of Berman screwing with our perceptions of time. “I'm afraid I've got more in common with who I was then who I am becoming,” he sings in Black and Brown Blues. The song and the poem seem to run on parallel train tracks; Black and Brown Blues is about a protagonist who can't even leave the house because he can't decide upon the right footwear, and this quandary is already hinted upon in Cassette County, where he wakes up thinking “feeling is a skill now.”

It's just that the Then is getting larger all the time. There's the personal Then, the sort that can bring on world-weariness and the feeling that you've seen it all before. To grow old is to bring on an epidemic of nostalgia: there is an ever-increasing part of the world that used to be better.

More overwhelming yet is the universal Then, which commenced roughly when Herodotus decided the events of the Greco-Persian War should not be lost to time. From then on, we kept track of more and more of what was happening around us, and have kept track from more and more angles, through more and more lenses. If the Greco-Persian War was happening now, it would be reported through a kaleidoscope of Herodoti, all taking cues from their own methodological church.

I sometimes feel there is too much scholarship, and too few subjects to divide among the hungry academics. When I was studying linguistics this was the thing that troubled me most, all these articles of mind-boggling specificity (“laryngeal complexity in Otomanguean vowels” would be a good one); it seemed more like entomology than linguistics. It must have been while I was struggling with my BA thesis that I read Kingsley Amis' Lucky Jim and the following passage perfectly summarised my feelings:

Dixon looked out of the window at the fields wheeling past, bright green after a wet April. it wasn't the double-exposure effect of the last minute's talk that had dumbfounded him, for such incidents formed the staple material of Welch colloquies; it was the prospect of reciting the title of the article he'd written. It was a perfect title, in that it crystallised the article's niggling mindlessness, its funeral parade of yawn-enforcing facts, the pseudo-light it threw on non-problems. Dixon had read, or begun to read, dozens like it, but his own seemed worse than most in its air of being convinced of its own usefulness and significance. ‘In considering this strangely neglected topic,’ it began. This what neglected topic? this strangely what topic? His thinking all this without having defiled and set fire to the typescript only made him appear to himself as more of a hypocrite and fool. ‘Let's see,’ he echoed Welch in a pretended effort of memory: ‘oh yes; The Economic Influence of Developments in Shipbuilding Techniques, 1450-1485.’

(Apart from being hilarious, Amis in the process has also pinpointed another characteristic of this “niggling mindlessness”: you know you are dealing with an ‘entomoligical’ article when it starts by at length convincing you of its own purpose.)

Chris Anderson has eulogised the coming of the long tail – “selling more of less” – in the business world, but the scholarly world is hardly exempt, and it's easy to see why. From Herodotus on we piled on the knowledge, and fewer and fewer of it got lost. Moreover, we have grown exponentially in both numbers and leisure time, leaving more people with nothing better to do than write about shipbuilding techniques in the 15th century.

I realise I am repeating myself here, but I think it is worth pressing this point: we are paralysed by the enormous weight of the written past. We don't have to actually read about it. Knowing it's floating around somewhere is enough. The situationist Raoul Vaneigem touched upon this in The Revolution of Everyday Life:

As Rosanov says, men are crushed under the wardrobe. Without lifting up the wardrobe it is impossible to deliver whole peoples from their endless and unbearable suffering. It is terrible that even one man should be crushed under such a weight: to want to breathe, and not to be able to. The wardrobe rests on everybody, and everyone gets his inalienable share of suffering. And everybody tries to lift up the wardrobe, but not with the same conviction, not with the same energy. A curious groaning civilization.

Thinkers ask themselves: "What? Men under the wardrobe? However did they get there?" All the same, they got there. And if someone comes along and proves in the name of objectivity that the burden can never be removed, each of his words adds to the weight of the wardrobe, that object which he means to describe with the universality of his 'objective consciousness'. And the whole Christian spirit is there, fondling suffering like a good dog and handing out photographs of crushed but smiling men. “The rationality of the wardrobe is always the best”, proclaim the thousands of books published every day to be stacked in the wardrobe. And all the while everyone wants to breathe and no-one can breathe, and many say “We will breathe later”, and most do not die, because they are already dead.

And I haven't even discussed the Internet yet...

All these citations are from what Jaron Lanier now calls antenimbosian times (before the infamous cloud). But if Silicon Valley statistics are anything to go by, Berman's scales will have shifted heavily since he wrote his poem in 1999. Our world, by now, must be 99% Then, leaving only one fricking percent of Now. And even knowing this to be true, we have to “keep moving with the times”, have to remain in that one-percented Now that is simply too small to contain all of us. For if you set foot in the luxuriously spaced Then, you will be branded a Luddite. There is a whole world beyond the wardrobe, but we are all stuck here underneath it (what Vaneigem as a Marxist revolutionist envisioned, of course, was a wardrobe filled with ideologies, most notably capitalism).

The Forgotten Works

Talmudic Jews have a law that forbids a man to remind another man of his former self. It is the me of the Now you are talking to, so that is the one you need to address, they argue. Perhaps, just perhaps, it might be time for life to inch towards being “a sleep and a forgetting” again. Richard Brautigan certainly believed oblivion to be the answer. Brautigan, of course, was of a generation and a world which had more trouble than ever before “managing” the past, was of a world wrecked by World Wars. His solution was to forget, to be the inebriated outcast at the edge of civilisation. In his novella In Watermelon Sugar he describes a utopia that is predicated on erasing the past. Brautigan's is a republic that has outlawed all writing and all objects tainted by history to a place called the Forgotten Works:

The Forgotten Works just go on and on and on and on and on and on and on and on and on. You get the picture. It's a big place, much bigger than we are.

(This sounds a little like the vision David Byrne has for the Internet.)

In the book, everyone who happens upon this place becomes enchanted, unchaste. There are tigers who are very wise but who munch on the past, and inBOIL and his gang who start to live there and are thus fixing the broken mirror from Berman's poem (“what does a mirror look like when it's not working”). The inBOILers reflect Brautigan's protagonists back to them and it is not a pretty sight. Brautigan's republic is a kind of Garden of Eden, that can only function in absolute oblivion. One act of sin and the trouble starts all over again.

So, no, forgetting is not the answer. But neither will Total Recall be.

When history turns from narrative to data, there's trouble on the horizon. Narrative history can tell us that there were other, very different times in which people nevertheless displayed the same human (humane) affections and emotions. Data will only be an inescapable wardrobe crushing us, or at the very least our spirits, so that “we will breathe later, and we will not die, because we will already be dead.”

Or, as Berman has it: “One of these days, these days will end.”

This suction of the vacuum is what I kept feeling when I read Alejo Carpentier's The Kingdom of This World. Set amidst the power struggles of the Haitian Revolution, this novella is like an insidiously romantic old photograph, like the vague smears left by a voodoo spirit traversing the Hispaniolan island. Though Carpentier mostly follows the fate of one slave called Ti Noël, he moves restlessly across race and class, bunking for a while with Pauline Bonaparte, Napoleon's little sister who was the wife of the French general stationed in Haïti (then Saint-Domingue), and with King Henri-Christophe, the first Black King. Carpentier seems both unable and unwilling to keep the narrative tight and tidy. From the start, there is a sense of general unhinge to the story, a sense that every footstep set will be doubled back upon. Indeed, to an ignoramus like me, the names of the various black rebel leaders blur into one another: Macandal, Bouckman, Henri-Christophe. Never has a novella so clearly shown what George Orwell preached in Animal Farm - that the revolters of today will be the tyrants of tomorrow. Ti Noël, after a brief stint in Cuba, comes back with a heart brimful with hope to gaze upon the first Negro-led nation, and is shocked to see the blacks whip and flagellate the other blacks. “It was as though, in the same family, the children were to beat the parents, the grandson the grandmother, the daughters-in-law the mother who cooked for them.” It was the demise of a dream.

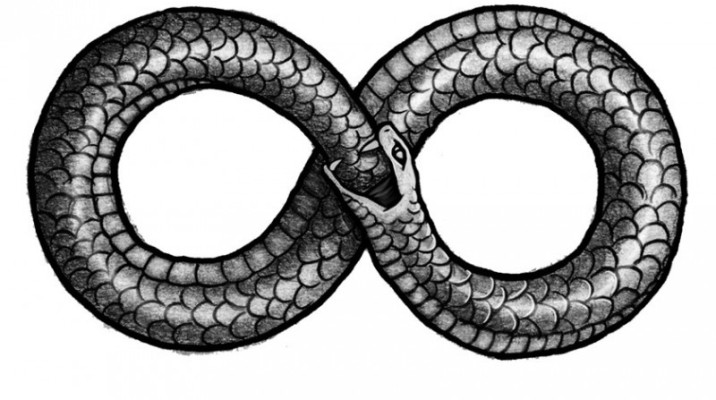

This suction of the vacuum is what I kept feeling when I read Alejo Carpentier's The Kingdom of This World. Set amidst the power struggles of the Haitian Revolution, this novella is like an insidiously romantic old photograph, like the vague smears left by a voodoo spirit traversing the Hispaniolan island. Though Carpentier mostly follows the fate of one slave called Ti Noël, he moves restlessly across race and class, bunking for a while with Pauline Bonaparte, Napoleon's little sister who was the wife of the French general stationed in Haïti (then Saint-Domingue), and with King Henri-Christophe, the first Black King. Carpentier seems both unable and unwilling to keep the narrative tight and tidy. From the start, there is a sense of general unhinge to the story, a sense that every footstep set will be doubled back upon. Indeed, to an ignoramus like me, the names of the various black rebel leaders blur into one another: Macandal, Bouckman, Henri-Christophe. Never has a novella so clearly shown what George Orwell preached in Animal Farm - that the revolters of today will be the tyrants of tomorrow. Ti Noël, after a brief stint in Cuba, comes back with a heart brimful with hope to gaze upon the first Negro-led nation, and is shocked to see the blacks whip and flagellate the other blacks. “It was as though, in the same family, the children were to beat the parents, the grandson the grandmother, the daughters-in-law the mother who cooked for them.” It was the demise of a dream. It is therefore no surprise that snakes and serpents feature heavily throughout the book. There is talk of “King Da, the incarnation of the Serpent, which is the eternal beginning, never ending,” as well as the Cobra of the holy city of Whidah, “the mystical representation of the eternal wheel.” Da is short for Damballa, the Vodou God of the Sky, the primary Vodou God. Snakes and serpents feature prominently throughout many religions across the globe. Most (in)famously, the snake in the Garden of Eden seduced Adam and Eve into taking a bite of the apple. This event was the introduction of sin but simultaneously the introduction of time, it was the Kingdom of Heaven tumbling down to earth. Earth, which is another thing the snake symbolises. Stealthily and steadily, it creeps along, always touching base. Most of all, though, the snake is associated with cycles and renewal. It sheds its own skin to be born again, and is often represented as a circle, biting its own tail. The snake is therefore the great adversary of any revolution, a symbol of inevitability, of always ending up back where you began. Indeed it begs a question Carpentier dutifully asks: “Could a civilized person have been expected to concern himself with the savage beliefs of people who worshipped a snake?” Probably not.

It is therefore no surprise that snakes and serpents feature heavily throughout the book. There is talk of “King Da, the incarnation of the Serpent, which is the eternal beginning, never ending,” as well as the Cobra of the holy city of Whidah, “the mystical representation of the eternal wheel.” Da is short for Damballa, the Vodou God of the Sky, the primary Vodou God. Snakes and serpents feature prominently throughout many religions across the globe. Most (in)famously, the snake in the Garden of Eden seduced Adam and Eve into taking a bite of the apple. This event was the introduction of sin but simultaneously the introduction of time, it was the Kingdom of Heaven tumbling down to earth. Earth, which is another thing the snake symbolises. Stealthily and steadily, it creeps along, always touching base. Most of all, though, the snake is associated with cycles and renewal. It sheds its own skin to be born again, and is often represented as a circle, biting its own tail. The snake is therefore the great adversary of any revolution, a symbol of inevitability, of always ending up back where you began. Indeed it begs a question Carpentier dutifully asks: “Could a civilized person have been expected to concern himself with the savage beliefs of people who worshipped a snake?” Probably not. Perhaps it is to such a background that we can understand why King Henri-Christophe, that first of Black kings, was more inspired by Napoleon than by endemic rulers and gods. He wanted to make his mark upon place and time, and in the north of Haïti, near Milot, he had his slaves built him a palace and a citadel. The Citadel La Ferriere, which Carpentier calls “a mountain on a mountain”, rose above the palace Sans Souci. Henri-Christophe chose elevation, that easiest of symbolisms, to help him on his way to immortality, to help him stand “on his own shadow”. Now, two hundred years later, as you might guess, all that is left of those palaces are ruins. A UNESCO heritage site. Suitable for photographs only.

Perhaps it is to such a background that we can understand why King Henri-Christophe, that first of Black kings, was more inspired by Napoleon than by endemic rulers and gods. He wanted to make his mark upon place and time, and in the north of Haïti, near Milot, he had his slaves built him a palace and a citadel. The Citadel La Ferriere, which Carpentier calls “a mountain on a mountain”, rose above the palace Sans Souci. Henri-Christophe chose elevation, that easiest of symbolisms, to help him on his way to immortality, to help him stand “on his own shadow”. Now, two hundred years later, as you might guess, all that is left of those palaces are ruins. A UNESCO heritage site. Suitable for photographs only.